When I picked my study abroad destination for the Take the World by the Horns program, I felt confident in my ability to adjust to Panama. I had four years of Spanish classes behind me, and growing up in Southern California meant I heard Spanish on sidewalks, in stores, and on the radio.

Confidence doesn’t always translate. My first morning in Panama City, a local greeted me with: “¿Que xopa?” — and I froze. The words weren’t in any grammar book I’d ever opened or phrase list I’d practiced. For a second, I doubted everything I thought I knew.

Tranquila (Relax)

By my second week, I had a notebook full of environmental studies terms and cultural anthropology notes, but the word that stuck most was one I learned outside class: “tranquila.”

It came to me first in a downpour, when the skies cracked open over Avenida Central and my notebook ink began to run. I tried to rush between stalls, panicked I’d miss our visit to the Biomuseo. A jewelry vendor just smiled and said, “tranquila,” or relax.

I heard it again a few days later, this time at the mall while I was buying supplies for my dorm. Back home in the United States, I was used to quick scanners, self-checkouts, and moving through errands in minutes. Here, the process stretched on.

Barcodes weren’t scanning, bags were slowly packed, and lines were moving at a crawl. At first, I tapped my foot and checked the time. Then I realized this is the pace, and nobody else was impatient. People greeted the cashier, chatted, and lingered.

That’s when “tranquila” sank in. Panama runs on its own clock. It’s not wrong, just different. You learn to let go of the stopwatch in your head and adjust to the rhythm around you.

Buen Provecho (Bon Appétit)

If “tranquila” taught me patience, “buen provecho” taught me presence.

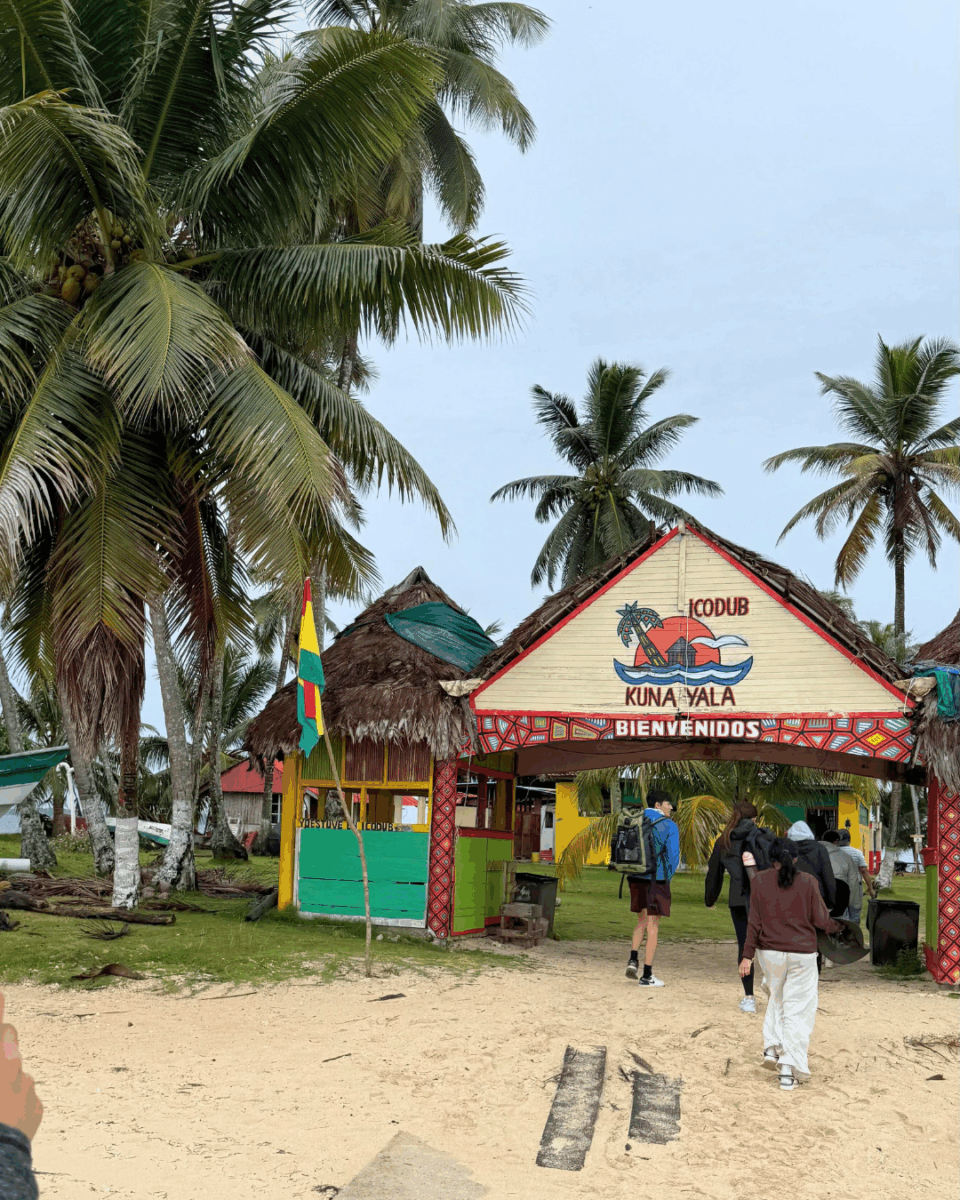

In the San Blas islands with the indigenous Guna Yala community, meals were as much about gathering as they were about eating. We enjoyed fresh fish pulled from the sea that morning, along with rice and “patacones” (slices of unripe plantains), on the tiny island where we stayed for our first overnight excursion with our anthropology class.

Before we even picked up our forks, someone would say “buen provecho” — like “bon appétit” — reminding us that sharing a meal meant sharing space, time, and gratitude.

Weeks later, during a cooking class in Panama City, I found myself repeating the exact words to my classmates as we sat down to try the Panamanian tamales (corn dough wrapped and steamed in banana leaves) and “carimañola” (yuca dough, stuffed with ground beef) we had just prepared.

The phrase had naturally slipped into my vocabulary, but more importantly, it had also become a part of how I thought about food. “Buen provecho” had already become part of how I felt about meals, as moments to pause and connect.

A la Orden (At Your Service)

At Merca Panamá, the city’s bustling wholesale market, I stumbled through my slow Spanish while asking about a stack of “maracuyá “(Panama has the absolute best passionfruit). The vendor listened patiently, nodded, and answered my questions with a smile. When I thanked her profusely, she replied: a la orden.

It translates literally to “at your service,” but it’s warmer than that, like a way of saying, “I’m here for you, don’t worry.” In those early weeks, when my Spanish felt clumsy and every sentence took effort, hearing “a la orden” felt like reassurance. There was no judgment for imperfect words, but instead, I was being welcomed into a conversation.

By the time I left the market with fruit in my bag, I realized that “a la orden” was an attitude of generosity that showed up everywhere in Panama: in neighbors holding open doors, in classmates helping to translate, and in people taking the time to listen, even when I spoke slowly.

Takeaways

Looking back, my Spanish cheat sheet isn’t really about definitions of words. It’s more about what those words taught me. None of these lessons came easily. They arrived in rainstorms, crowded markets, and conversations where I stumbled for the right words. But that’s what study abroad gives you: the gift of being uncomfortable, and the chance to grow comfortable within it.

Panama doesn’t let you stay in your comfort zone. Instead, it asks you to adapt, to listen, to laugh at your mistakes, and to see that another place and another language have something to teach you. That’s the beauty of being here. Every moment of discomfort becomes a lesson.

That’s why I’ll carry these phrases with me long after I leave, as reminders that the best parts of study abroad start when you step into the unfamiliar and learn to make it your own.

This post was contributed by Dhriti Mangaraju, a Global Ambassador for Fall 2025. Dhriti is a freshman participating in the Take the World by the Horns program in partnership with the School for International Training in Panama City, Panama.