When I exit Boryspil Airport, setting off to my home for the next seven weeks, it is 90 degrees Fahrenheit. The heatwave in Kyiv should end in the coming days, but until then, the city boils. On the drive to my home outside the center of Kyiv, I catch flashes of the Roman alphabet, but most everything I see is written in Cyrillic lettering, be it Ukrainian or Russian. The freezing hot ball that formed in the pit of my stomach, after leaving my dad behind at airport security nearly 16 hours ago, tightens. I wonder to myself if I will make it through all seven weeks of my program. This blog post is for students like me, that wonder what it is like to travel with mental illness.

Throughout my whole life, I’ve suffered from anxiety, depression, and general mood swings. It waxes and wanes, but I always feel the thrum of instability in my body. My medication keeps me on an even keel, but it did not prepare me for the visceral experience of culture shock. Before leaving, I attended all of the seminars UT provided, acquired all my medications for seven weeks, and thought that my action plan and my excitement would overshadow any worries I could have. But it wasn’t not enough to quell my anxiety. The key for students with mental illness is to understand that you are going to feel what you’ll feel, no matter what. But how you react and behave afterward defines your time abroad.

My first night in Kyiv, Ukraine–eight hours ahead of Texas, with no air conditioning–feels vastly different yet perplexingly similar. I’m practicing my breathing exercises and chanting a sort of hymn about the ephemerality of my mental anguish. My mind, wishing I were back in Texas, plays on repeat a song from a childhood TV show, SpongeBob SquarePants. I am homesick. The bathroom is unfamiliar, I feel obligated to eat all food given to me, I fry my American extension cord in the European outlet, and once again, there is no air conditioning. I take half a pill of my emergency anxiety medication, which is separate from my normal antidepressants. I proceed to sleep for 12 hours.

I write this on my second day in Ukraine: you’re going to be okay. Studying abroad, even with UT’s best efforts to prepare you, is hard. It’s difficult for people who crave routine and stability to wake up in a foreign bed in a foreign land, eat foreign food and then speak a foreign language. I don’t deal well with change and yet I flew across the globe to learn. You know what, though? It’s already worth it.

When my host mom took me to the supermarket, I had an opportunity to try foreign snacks and experience a Ukrainian grocery store (along with its pricing, which my U.S. dollars-brain is still figuring out). As my host grandmother and I sat on a bench watching her grandson play in a детская площадка (detskaya ploshchadka or playground), chatting about anything that I had the vocabulary for, I realized that this experience is good for me. It’s one thing to conceptualize and to encourage yourself to go abroad because you know it will help you grow, will add to your resume, will be a fun time, what have you. It’s an entirely other thing to experience it. That’s why I think that students, especially those with mental illnesses, should study abroad. You should experience this.

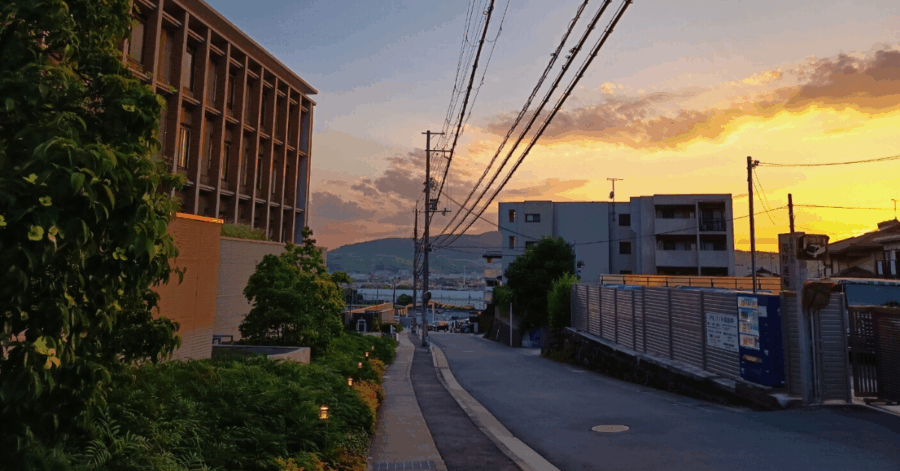

When I’m by myself and my throat closes a little, when my insides churn with unbridled and irrational terror, I breathe in, and I breathe out. I had known that Ukrainian and Slavic countries have close-knit communities, but now I know because I’ve walked through a neighborhood where a smattering of bazaars, supermarkets, old Soviet apartment buildings, schools, and parks are all within reach. Likewise, I had known that air conditioning is not common here, and now I know that air conditioning is the thing I miss the most about home. Many aspects of life require hands-on experience. The opportunity to see with my own eyes, hear with my own ears, and process the beauty and raw splendor of Ukraine with my own anxious brain is not lost on me. I encourage students struggling with mental health to take on the challenge of practicing their gratitude to the nth degree. Intrusive thoughts will tell you all day about how you need to go home, how you’re not meant to be here, or how you’re not capable of making it on your own. You are capable. You’re meant to be here. You’re going to go back to America at the end of your time abroad and be a fuller person for it.

A piece of advice: lean on your support systems. My parents, my partner, and my friends from home are all privy to my emotions and my impressions. Remember that UT CMHC is here for you, too; we’re already used to Zoom, so the online format is more convenient than anything else! If you’re staying with a host family, like me, then please rely on them. They signed up to home you, to feed you, and to help you during your time abroad. When my mind was shutting down after thinking none of my power converters or outlet adapters were working, my host mom calmly helped me. We reset the circuit breaker for my room and ура! (hurray!) they worked. You’re going to feel very lonely when you first get here, and likely still for the first week or two. It’s natural even though it quite frankly sucks. In spite of this, please, please remember––you’re not alone.

Tomorrow I will use the metro system for the first time in my life. I’ll begin formal Russian lessons separate from the immersive nature of a homestay. I’m in the middle of drafting a research paper on security and society that will likely be published by the end of this summer. I don’t know what to expect except the shattering of my expectations. Despite my trepidations and the feeling in my stomach telling me the world is ending, I’m excited for the adventures of the next seven weeks. This is only the beginning! I can’t wait to take y’all along with me. До следующего раза! (Do sledyushchevo raza! Until next time!)

P.S. When there’s no AC, ask for a fan and open the window! You’ll get through it!

This post was contributed by Kylie Heitzenrater, a Global Ambassador for summer 2021. Kylie is a Linguistics and International Relations & Global Studies double major studying abroad in Kyiv, Ukraine.